I’ve had many different visions for this conversation—recorded, or an essay, or a profile-esque exploration of all the beauty and intelligence that Carlee Gomes holds with total ease. What’s ended up coming to fruition is a Frankenstein–ed conversation between Carlee and I about feminine performance in our modern capitalist landscape (we talk about this basically constantly in private) with Paul Verhoeven’s Showgirls as its guiding compass. This conversation is out of order, sub-sectioned, and often cyclical. I am the person I am by having conversations with Carlee in this way, so I am happy to share something that reflects how we communicate in private.

(All moments where there are scare quotes were deeply, deeply emphatic visual finger-quotes from our recorded conversation. All italics are deeply felt.)

Carlee’s essential piece on sex scene discourse, The Puritanical Eye: Hyper-mediation, Sex on Film, and the Disavowal of Desire, can be found here.

Veronica: This is so weird now, but I knew you as the Showgirls lady before I knew you.

Carlee: That’s so weird to me.

Veronica: Do you have a basic thesis on why you love it?

Carlee: On a really non-cerebral level, I grew up with Elizabeth Berkeley on Saved By The Bell. The first time I saw Showgirls was on TV, which I don’t count. They draw the bras on, it’s two seconds long. But I was like, “Oh my god, that’s Jessie Spano.” I was so captivated by her. When I watched it for the proper first time in college, it was just clicking for me. There was something about the relationships between the women, the femininity, it just spoke to me on a level I didn’t have the language for yet. I knew it understood me and it helped me understand me. The more time I’ve spent with it the more I feel it’s a brilliant, high feminist text.

SOME THOUGHTS ON FEMININITY, MOVEMENT, AND PERFORMANCE IN SHOWGIRLS:

Carlee: In the very first scene, the way Nomi’s make-up is done, the way she is holding her lips, the way she moves her body, already you are like, “This woman is sexualized.” The lens we are looking at her through is sexualized, and also she just exudes sex herself.

Veronica: Nomi’s performance of femininity has absolutely zero passivity to me. Her performance is active from the jump, including, as you said, even the way she holds her mouth.

Carlee: There is a ferocity and an explosiveness to [Nomi’s] movement, but there’s also this sense — and I hesitate to use the word “childish”, because it’s not quite right — but she is, in a sense. Like, she throws tantrums. There is a sort of childishness to her reactivity, and that is expressed beautifully in the way she moves her body. She’s like a live wire. She’s always throwing elbows, gritting her teeth, hitting people, slapping things, and you get the sense that she can’t not move her body like that. We see that from the opening frames when she’s stomping across the parking lot. She’s about to fuck or fuck someone up.

Veronica: I think that’s the essential aspect of the presentation of femininity in this film. She’s not graceful, but she is hyper-feminine. I think Nomi has something about her that’s “girly”. But it’s not grace and it’s not delicate at all. Her dancing is almost aggro, and you have to adjust to the flavor of it. It’s all of these sort of staccato, rapid movements that she completes one at a time, almost as in a checklist. But she’s in an almost flow state, and she’s performing totally as herself.

Carlee: Yeah, the thing that is so important about both Elizabeth Berkeley and Gina Gershon is that both of them are professionally trained dancers. As a dancer watching this movie, the dancing is phenomenal. Their turnouts are great, their kicks are high; they’re really good dancers. What Berkeley is doing as Nomi—which are these sort of violent, live wire, angry moves–Marty the dance director says that “She’s all pelvis, man.” She’s all thrust and all pelvis. But she’s got it. The rawness of her performance is startling, but you also can’t deny that it is really compelling and intoxicating. And so, to Berkley’s credit, her being a trained dancer and being able to get on stage and communicate Nomi’s erraticness and the parts of her that are a little more rough around the edges is a fearless performance, specifically as a dancer. And you cannot deny the eroticism of it. When you see her do that private dance for Zack, like, it’s insane and it’s also crazy hot.

Veronica: Yes! You can’t not think about actual sex when you’re watching it. It feels like you are watching this specific character move as they would actually fuck.

[…]

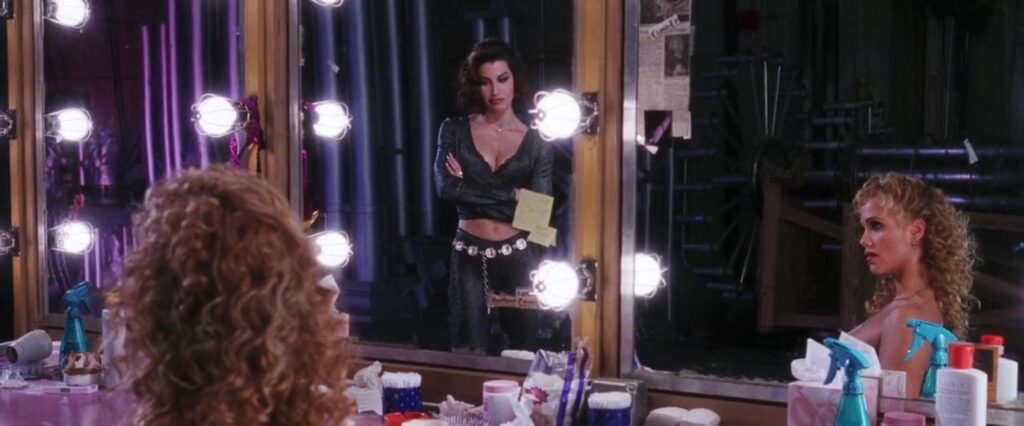

Carlee: One of the things that I really loved lingering on in this rewatch is the way that Nomi slows down in a couple of key moments in the film. When she first meets Molly, she’s been swerving in the truck and stomping around the freeway, she’s running through the casino, she’s throwing coins. And then Molly punches her, and then helps her up, and Nomi and Molly lock eyes and it looks like they’re going to kiss. Nomi is exhaling for the first time since we’ve seen her on screen. And then the other time that she really stops is when she and Cristal first meet eyes, when Cristal is looking at her through her dressing room mirrors. They slow down, they stop, they lock eyes, and there is chemistry there. You know, people love to talk about how shitty the performances are, but that’s like baby-brained shit; there’s so much detail in the physicality of the performances, particularly between the women. But we also see how Nomi holds herself and moves her body related to men. She’s thrashing constantly when she’s around men: the club owner at the Cheetah, Zack, guys that are swatting at her at the club. She is constantly on the offensive, and when she’s not it’s when she’s at lunch with Cristal, or when she locks eyes with Molly and tells her, “I love you.” This is where the film is telling us, “This is where real connection is.”

Veronica: I think a lot about a moment where Nomi is still at The Cheetah and someone smacks her ass, and she says something semi-polite to him, but then throws daggers in the other direction. It’s in those tiny moments where she’s at best ambivalent and usually loathing the men she’s interacting with where we get a lot of insight into Verhoven’s satirical setup, because it bursts the bubble for you. Showgirls doesn’t let you convince yourself that you would be different or above transactional gender and sex relationships.

Carlee: Completely. I think post-MeToo I feel like a lot of finger-quotes “normal guys” are like, “I’m the good guy”, right? And they don’t want to confront that they’re just like any other guy in the club.

Veronica: I also wanna talk about Nomi’s line delivery, because to me she gives almost a pull-string doll delivery. Everything comes out similar, and often very angry. She has no issue coming out shrill, or intense, or argumentative, which is not necessarily what you want if you’re a man looking for a passive, idealized sexual situation. I find that so sexy. I find that to be the best part of her character.

Carlee: That’s the way I read the performance of her lines, that’s how I read her interactions with James. He’s a black man who works bullshit jobs in Vegas, so another oppressed class that this city runs on. He runs game on her, yes, but from the moment he meets her he’s telling her the truth. He’s being real with her about the nature of the landscape that they’re in, her role in it, the talent he sees in her, and he’s trying to get her to see the machinations of everything and to see herself as more than what everyone says she is. James is like, “What the fuck are you talking about? You sound like a t-shirt: shit happens, life sucks, like what are you saying?” But that doesn’t detract from his attraction to her. He’s someone comfortable existing beyond the guardrails of the roles they’re all supposed to play. He’s able to see her, even though she’s not doing the things a woman is supposed to do and say. He gets her. And that’s attractive to me.

SOME THOUGHTS ON FEMININITY AND TRANSACTION IN SHOWGIRLS:

Veronica: There’s this dichotomy between [Nomi and Cristal] where Cristal is the more seasoned one, and is more comfortable with being perceived as a “hooker” — to use the term they do in the film — while Nomi has actually been in full service sex work and is repulsed by that accusation. But in a way, Cristal actually understands the selling of sex better in the sense that she’s selling the fantasy of something poised and chic and glamorous in a very classical sense, while Nomi is all immediate and reactive.

Carlee: 100%. And Cristal’s performance is more seasoned and more chic. It’s also more masculine. In every situation she can, Cristal is exerting her sexuality but also a very masculine power dynamic, even when she is dealing with men. This is why Nomi and Cristal clash, but are also drawn to each other. Nomi says from the jump, “I’m never going to be you, I’m never gonna be like you.” And Nomi never really does step into Cristal’s more masculine power. Cristal does things like grooming the girls underneath her, or paying for things in a way a man would. She’s very much like, “I’m taking you out to lunch, I’m getting you drunk, I’m going to play with your nipples like the dance director would.” Cristal fully embraces the demands that the consumer landscape asks of her, which is that if you want to sell your sex, you have to act “like a man”.

Veronica: Yes! I think that’s another one of Cristal and Nomi’s key differentials. Cristal is playing the system, she’s looking to win. And in a way, I find Nomi to be like the ideal consumer. She wants everything fast, and best, and her way. And if it’s not going her way immediately, she’s going to flip the fuck out. She’s going to eat how she wants, she’s going to fuck how she wants, and she doesn’t fuck with who she doesn’t want to fuck with even if it would technically or financially benefit her long term.

Carlee: Her being a live wire and, like, not interested in the artifice, is what is threatening, but then there’s also so much about her that is — I don’t want to say playing up artifice, because I think it’s wrong to say that her hyperfemininity is artificial —

Veronica (interrupting): —Because it kind of feels like it is her! It is her essence!

Carlee: It is her essence.

[…]

Carlee: Verhoven’s whole thing is like satirizing the transactional nature of sex in America by heightening it, and then also reminding us that we are still a puritanical society at heart. Like, we’ve relegated this specific place to the desert, right? This city [Vegas] is literally what this country runs on, just in a bouillon cube. And yet, we’re not supposed to acknowledge it. Audiences respond by saying, “Don’t remind me that we pay for sex or that we pay for the fantasy of a sexual experience with a girl or a woman that looks like Nomi. I don’t want to be reminded of that. I don’t want to be reminded that there are transactions driving women’s survival.” And so Nomi—in that private dance [with Zack and Cristal], dancing the way that she does on stage, fucking the way that she does—it’s all confronting people with not only the spectacle of sex as a consumer trade and an industry in America, but it’s also confronting people with the reality of the banality of that exchange, right?

[…]

Carlee: What does she want the whole time? She asserts at the beginning to the very purposeful Elvis doppelganger she hitchhikes with, “I’m not a hooker, I’m a dancer.” She’s already, like, declaring to us that she wants to be seen, and she wants to be seen authentically to who she feels she is and knows herself to be. And the people that actually see her, as in that specific person Nomi, not a type or product, are the ones that are inexorably drawn to her. And that is something the film understands about attraction and desire and what is erotic. It’s not a person playing into an archetype, but a person using assets of an archetype to express things that are not bound by archetypes and that are wholly realized, authentic, and singular to that person. And people that get that are like, “That’s attractive and I’m attracted to you specifically.”

Veronica: What she wants isn’t even antithetical to the capitalist dream. She’s like, “I want to be super famous and make a ton of money and be the most beautiful, and do it as me.” But because she’s this aggro-Barbie who can’t really hold a conversation the way men want her to, who’s going to roll her eyes, who’s going to thrust around instead of move with grace, she can evoke a response of, “That’s not fair” when she succeeds at moments on her own terms.

Carlee: Nomi is playing the game, but she is playing it wrong. That is the most succinct summation of her character that I’ve ever heard.

Veronica: It’s funny because she’s not even in a place where hyperfemininity isn’t allowed. But because she’s doing it “too much”, because she’s in excess in the most excessive place in America, there’s suddenly a boundary that’s there in a place that’s supposed to be boundaryless. Nomi throws all of our belief systems around sex and selling sex and femininity into whack when the way she dances and performs is “too far”.

Carlee: This film taking place in Vegas and making the statements it’s making about American political, and economic posture in the ‘90s and broadly as the country’s project is entirely intentional. There’s that conflict between boundaries in a place that’s supposed to be, like, total fantasy and secret. That contradiction is there to remind us that the system is built on contradictions, it’s built on the things that we are told to not pay attention to. And why Verhoven, I think, is so successful as a filmmaker — not necessarily materially, but I think artistically — is because his films are all about confronting us with those contradictions. This whole movie is about how you want the woman who’s, like, dolled up, eyelashes, nails, wants to fuck all the time, is a sex doll, doesn’t complicate your notions of power or make you feel dumb, you want her to be covered in glitter and totally hairless. Here is that woman and also she’s all these other things that we expect her not to be but also are directly tied to the things we’re attracted to. There’s a shot when they first pull into the casino parking lot when Nomi has hitchhiked into Vegas. There’s this wide shot, they swerve into the parking lot, and the one sign that we see above the car is a giant light-up sign that says HUGE STRAWBERRY SHORTCAKE: $1.50. That being on the sign when they pull into Vegas, to me, encapsulates what the whole film is about. They’re talking about “food”, sure, but no, they’re talking about women, they’re talking about sex, they’re talking about pleasure, they’re talking about all of it. Pay for it and you can have it and then we’ll go about our business.

Veronica: I think we should talk about the notion of “purchasable” in Showgirls, too.

Carlee: There are all of these sequences in [the movie A Chorus Line] where we are confronted with the fact that these people are like slabs of meat, but they are also these hyper-proficient machines, and they are judged as both. There’s a scene in Showgirls that mimics this, where they’re going down the line and talking about everyone’s physical maladies. They’re like “You look like shit, you need to fix your hair, ” and it’s this reminder that these people are products, not humans. It’s a reminder that even though we are told, “You get to be special in America”, you don’t. Especially if you are working in a body trade like sex work or dance. The next thirty seconds of the scene, the words that are being screamed at these women as they dance — Verhoven is not pulling punches here — is, “Sell! Sell your bodies!” The film isn’t just saying that this is transactional, it’s saying not only is this transactional, but it’s so ugly and so dehumanizing and so brutal and you still want it. The beautiful flourish of the audition scene is that it is over-the-top, dehumanizing, disgusting, they’re giving her ice to put on her nipples, we’re supposed to be repulsed by all of that. And at the same time, watching Elizabeth Berkeley in hot purple snake-skin and bright pink with her tits bouncing around while she hits these moves perfectly, you’re turned on by her performance. This scene encapsulates the entire contradiction of this project: here is all of this ugliness, here is the reminder that all of this is transactional, all of this is about commodities and capital, and also you still are drawn to and totally turned on by this woman, by these bodies, by this performance, and you want it.

Veronica: For Nomi, what she wants is to be the most looked at. The wins she has, especially in that scene I would say, are enthralling, and the payoff is the same over and over. It’s like, “I’m going to get to see Elizabeth Berkely dance again!” Nomi being seen the way she wants to and you getting to see that is this same feedback loop over and over and over, but instead of feeling satisfied you get that sort of sugar crash excess of: “This is costing so much for so little for this woman.”

Carlee: Yes! It mimics consumer cycles, right? It mimics the mania of advertisement loops. You get the thing, you have the cereal, you buy the shirt, and then you’re like,“That didn’t solve my problems.” There’s the fleetingness of the high that comes with these dopamine cycles that the film runs on, and that also our consumer landscape runs on. I don’t think it’s a mistake that Verhoven never lets us settle into any satisfying conclusion, even throughout the film. There’s an inexorable quality to this film, right? Everything feels sort of fatalistic, and that’s because it is for these women and for the people trapped in the machine of capitalism. What happens is only within your control to a certain degree. The film has this rhythm that mimics that and asserts this fatalistic quality, but also gives us some of these highs we get when we buy a thing or eat ice cream or whatever. But like it’s not real nourishing complete satisfaction. She gets the part, she gets to be Goddess, she gets to fuck Zack. All these ostensibly good things happen, things that she wants, things that we as an audience know are coming and so we should be satisfied them, but the film does a really good job — and I think this is why people had the response they did — of not allowing us to ever feel satiated or satisfied. Because none of this is satisfying. Even when there’s an orgasm or some other grand climax, like the beating that takes place at the end of the movie, it’s not satisfying, it’s never fully realized or resolved.

Veronica: Totally. This is why I always struggle when people are startled or dissatisfied by the end. I always read it as, in a landscape where everything is purchasable, people begin looking for “unpurchasable” experiences. Whether that be severe violence or the revelations of Nomi’s past or peeling back layers of someone’s identity without their consent. It’s not satisfying because it’s upsetting and because it’s the way these things go. You reach a point of excess and consumption that you tap out on.

[…]

Carlee: For me, what this film Showgirls understands, is that transactions in and of themselves are not exploitative or problematic. It is the context within which those transactions happen that can make them exploitative, banal, or erotic and transcendent and an avenue for real pleasure. I think an example that’s maybe worth examining in Showgirls is the scene between Nomi and James back at his warehouse apartment. Throughout the course of that entire scene, there’s a constant exchange back and forth between the two of them. He’s buying her a burger, she’s letting him see this part of her breast — there’s a back and forth happening. What makes it not exploitative and not violent and consensual is that it is consensual. When you are denying that the transaction exists altogether, that to me is an avenue for exploitation, and that’s what capitalism wants us to do. It wants to hide that all of this is economy. But what makes the exchanges between James and Nomi more erotic and consensual is that neither of them are denying that they’re in a transactional exchange. The way that the transactions shift and escalate towards near sex is something that they’re acknowledging along the way, even if it’s not through words. I love the way I get to see transactions play out between those two. And it ends with her being like, “I’m on my period.” And she asks him to check.

Veronica (interrupting, again): I love that part.

Carlee: So, so good. A really important thing about this movie is it mentions periods and women talking about their periods several times.

Veronica: This is what I love about how [Showgirls] balances femininity. There’s so much performance, but it’s about the work of this feminine performance. They’re sweaty and they’re bleeding and they’re fighting and they have children and their make-up gets fucked up, and they still execute this insanely feminine performance.

Carlee: Yeah! When there is acknowledgment of the effort, when there is acknowledgment of the performance, there’s potential for something really erotic to take place for people who want it that way. But when you’re not acknowledging that, or when you’re deriding it… I’ll use Henrietta as an example of this. She is a vector for all of the ways we get to acknowledge the transactions of this place that we’re in. She’s cracking jokes about women being pieces of shit, smelling like garbage, having STDs — she’s constantly dehumanizing women in this space and calling attention to the commodification of this exercise. She’s there to be like, “You can laugh at this, I’m here to remind you you’re better than how debased and ugly and brutal all of this is […] You get to laugh at me and that makes you feel better about the fact that you’re actually injected into this whole thing that we’re doing.” The obfuscation of the transaction is part of the exploitation, but there’s also the hyperawareness of the transaction that says, “See, this is actually gross and you’re above all this.”

[…]

Veronica: I think Nomi is kind of this intersection of an ultimate fantasy where there’s a girl so beautiful, who also enjoys fucking the exact was the way you would want to be fucked.

Carlee: I want to build on that slightly, because I think yes, she fucks the way that we’re supposed to think someone hot fucks, but it’s slightly different. Like I would almost say that it’s less that she is fucking the way that we’re told the perfect woman fucks. The pool scene is a great example, in the sense that it’s over-the-top for a reason. She looks like a sex doll at a certain point, and that is not what we’re supposed to want, right? We’re supposed to want this kind of beautiful, sensual, Vaseline-lensed, really breathy invocation of female pleasure and desire, and Nomi is not that. To your earlier point, she is not graceful. She is raw-edged, she is aggressive, she is violent. In the evocation of being a blow-up doll or a sex doll, or in some other elements of her performance that feel a little more carnal and less idealized, that is reminding us that that’s what we want. We want something kind of ugly, and we want something kind of brutal, and we’re not supposed to want that.

Veronica: [Nomi’s] femininity is expressed in this very essentialized and most potent form, which should be peak sexual attraction, but actually off-puts some people around her. But James gets her and Molly gets her, and I see those characters as reflective of people in the audience who actually see her as a human person first. The way that she’s expressing and interacting are superficial markers to what she’s actually trying to express or get done.

SOME THOUGHTS ON THE BIG PICTURE, OR, CARLEE AND MY HYPER-FEMININITY OFFICIAL TAKES:

Veronica: I think I know your dreams and aspirations around sex and pleasure. Do you want to talk more about any dreams and aspirations you have for Adriana La-Cerva/Nomi Malone-core femininity [author’s note: this is a short of hand Carlee and I use to talk about the acrylic-nail, leopard print, obviously performed femininity that we are both very drawn to] and how we perform it and talk about it culturally?

Carlee: You and I are two women who genuinely (and I put some asterisks around this) genuinely get joy from the performance, the effort, and being consumed as hyper-feminine. Adriana La Cerva, Nomi Malone-core femininity and how we talk about it, perform it… It’s really hard to say, “No! I’m doing this all for me! The patriarchy didn’t inform me wanting to paint my nails this way and wear a leopard top and show my ass.” I don’t actually know if that’s true. There’s a part of me that, I think, likes to reclaim a certain amount of agency, and I like the idea of doing this for me and importantly, especially [in regards to] the movie Showgirls, because other women notice it. Molly and Cristal notice the effort that Nomi puts into her appearance. They notice her nails, they notice her make-up, they notice her clothes, they compliment her on them or they get jealous, whatever it is.

So, like, my performance of hyperfemininity, my embodiment of hyperfemininity, I’m not going to sit here and say I’m not socialized to think that that is desirable and therefore I get a dopamine hit from performing it because I know I’ll be rewarded. I’m not going to sit here and say that that’s not playing a part in it. It might be. But I also like to think that there is some reclamation of agency when I am saying, “This actually brings me pleasure because it feels good and it feels authentic to who Carlee is.” I have days where I feel like a lumberjack, and that feels authentic to me on that day, right? But I think deciding that my expression of hyperfemininity is not something I feel is expressing myself or something core and authentic to me is removing a certain amount of my agency as a realized woman who knows herself. It’s to say that this brings me joy. You know? I will also say, it would be wrong of me not to acknowledge that I get pleasure from the rewards that the system gives me for dressing that way or looking good. Getting rewarded for those things through the attention of men, through compliments of women, job opportunities, whatever it may be — if I ever reap benefits from “the system” for that performance of hyperfemininity, I do get pleasure from those rewards, but what’s more pleasurable to me is when I wear a leopard top and knee high patent boots and I feel like fucking Carlee, like I feel like me, and someone sees me and compliments me, I feel like I’m being seen. That’s what’s preferable to me. I feel like someone’s seeing Carlee and they’re appreciating it.

Veronica: I’m slightly paraphrasing from “Puritanical Eye: Hyper-Mediation, Sex On Film, and the Disavowal of Desire” [author’s note: if you somehow haven’t read this, you quite literally have to] but there’s a point where you say, essentially, that in our modern political and cultural state, “…films must serve as an expression of who we are.” I think there’s a modern tendency to resonate with not just films, but with characters, as a way of expressing our identity, “she’s so me”-esque memes, etc. Do you have thoughts on that in terms of not just our internal state, but our external one? What of the way we learn to fuck, flirt, dress, move?

Carlee: How does a completely or mostly mediated lived experience affect the way we not only perform identities, but also conceive of that which makes them up? Where do we draw inspiration from? Now, I would argue, where most people draw inspiration from is content, or at the very least media that is presented to us digitally. What does this do to our understanding of bodies in space, real space, embodied experience versus mediated experience? What does this do to our understanding of our own bodies and others’ bodies? Expression becomes further tethered to relational matrices which exist online, which are, whether we like to think it or not, inherently tied to algorithms, codes, things that are less spontaneous, less messy, less organic, less muddled, and nuanced and complicated.

Because the binaries that these systems run on — the systems of our digital spaces, and the digital tools that we use to communicate and express ourselves, don’t run on things that are not binary. They don’t run on things that are messy and nuanced and contain contradictions. They don’t support that kind of language. Even if we feel we are above an algorithm, we are utilizing media, content, images, soundbites that emanate from a system of order that is not organic. It’s deeply coded and algorithmic. Those things, ultimately, coming from a digital landscape can only go so far in terms of our identities as embodied. Like, fully embodied in real, tangible space. Not digital space. I would argue that that’s a bad thing. My entire thesis is on the suppression of the body and the suppression of our bodies being engaged is what leads us to further acquiescence of this system. But I also think it leads us to, like, a misery that comes from not fully being able to express yourself. Because part of how you fully express yourself is in an embodied language, in a physical, corporeal language. And that sometimes comes from art and music and books, it sometimes comes from images you see on TV or online, but it also comes from things that don’t fit into any of those boxes. So it’s a matter of not just the things that we utilize to express our identities falling short and keeping us inured to the system, it also creates an irresolution inside of us that we cannot name. I think the irresolution is not ever feeling fully realized or expressed as yourself.

Veronica: It’s interesting, at this point I wasn’t going to try and tie everything to Showgirls, but I think what people struggle a lot with Nomi particularly is that she’s inherently contradictory. In the reveal at the end of all of her various crimes, most of her rap sheet is soliciting for sex, and she absolutely refuses to be called a hooker. She wants to be the most looked at person ever, and doesn’t want to be fully seen or understood or have her identity revealed. These things are in perfect alignment with herself, but are contradictory to using language to define her. That “contradiction” is kind of what makes her immortal and impossible to pin down, because she simply rejects “getting got”, as it were. She’ll always just move to the next city.

Carlee: You’re right. The true expression of herself is full of things that do not subscribe to the equations of the system, right? The contradictions that you’re pointing out can exist in life, right? In some reality that isn’t constrained by capitalism. But because they do not adhere to the calculus of the system, and because they don’t use the integers of the system — or if they do, she uses them subversively — it’s irreconcilable. That she is a person who is fully expressing who she is is hard for us to digest when we are — and here I’ll go back to Mark Fisher, as I always do — confronted with our own capitalist realism. When we can’t think beyond the constraints of the system, someone like Nomi cannot be digested by us. A film like Showgirls cannot be digested by us. Humans have lived for millenia and there have been authentic modes of expressing yourself outside of the systems of capitalism for millennia. And we have to remember that what makes us human is our desire to self-express. It’s inherent in humanity. If we aren’t fully able to actualize that? We’re going to be some kind of miserable.

RAPID-FIRE QUESTIONS:

HF: What’s your biggest time suck online?

CG: Responding to every comment I get, and typically with multiple thoughts/sentences.

HF: Favorite curse word?

CG: “BITCH???” with aggressive question marks in my delivery, or if someone is really pissing me off, “gash” (we can thank the Brits for that one).

HF: Favorite perverted thing (it can be art, an object, a person, a sex act, whatever)?

CG: I absolutely can not pick a favorite and I can’t believe you would try to contain me in this way (jk ily), but I really love any painting of Caravaggio’s. He was incredibly perverted in some beautifully artistic and subversive ways and in some very problematic ways. I hesitate to call any sex act perverted, though there is of course a spectrum, but for me, something not perverted but quite essential, electric and sometimes elusive for me, is when someone makes me feel a perfect balance of objectified, worshipped, submissive but agent and captivating, slightly roughed up but also tended to and cared for, makes me feel like a slut and a goddess all at once, that just absolutely sets my entire soul on fire.

HF: A sex discourse you wish you could ban?

CG: I think you know my answer for this one, but it’s absolutely the “there shouldn’t be sex in movies” discourse. Although having it exist at all, I suppose, is important because it helps give relief to my ideas on the matter and affirm things about the state of our cultural, material, and political realities that express themselves here and elsewhere.

HF: Favorite book from childhood?

CG: The book I taught myself to read with was a Clifford the Big Red Dog book, but my favorite books growing up were the Bailey School Kids books.

HF: Song of the spring?

CG: Currently? “luther” by Kendrick Lamar, and when I am feeling more piney “Crybaby” by SZA. But this week I have been listening to Jackie Shane’s “Comin’ Down” nonstop and Bad Bunny’s DTMF a lot–the run from TURiSTA through LO QUE LE PASÓ A HAWAii is pretty perfect. Honorable mention “I Don’t Belong” by Fontaines D.C. (I literally can’t pick one of anything).

HF: Do you call it a journal or a diary?

CG: Both, depending on who I’m talking to.

HF: Person dead or alive that you would ask to dinner with the sole purpose of getting to throw a drink in their face?

CG: Every American president.

HF: Ideal nap length?

CG: Girl, I don’t nap.

HF: Best time to write?

CG: Like 10pm before a deadline. This is how I wrote most of my college papers too.

HF: Worst place to edit writing?

CG: A coffee shop. I really don’t get how people can do email job work in these joints.

HF: Any opinion on any movie ever?

CG: David Cronenberg’s Crash is one of the best movies in the history of cinema, Coffy contains one of the most politically, racially, and sexually incisive “food fights” in any film, and old Hollywood musicals look like living dreams.